Manuscript Variants and The Origins of Cíannachta Glinne Geimen

Eystein Thanisch

ORCID: 0000-0003-2819-5519

To what is this the beginning?

This is the first of a series of blogposts that are intended to illustrate the kind of decisions we have to take when encoding medieval Irish genealogies as RDF, as well as what can be done with the results. This can get complicated and require editorial judgement. We are working, after all, with pre-modern manuscript sources. Their compilers are influenced by the political implications of the past, imagined or otherwise, in their own society and struggling to understand the textual tradition in which they worked.

The Genealogies and IrishGen

For introductory reading on the genealogies, we recommend Nollaig Ó Muraíle’s published lecture, The Irish Genealogies: Irish History’s Poor Relation?, and Matthew Holmberg’s PhD thesis, ‘Towards a Relative Chronology of the Milesian Genealogical Scheme’ (pp. 3–54). For an overview of IrishGen and our use of RDF, see the project README. All our data is available in our GitHub repository.

Cíannachta Glinne Geimen

Today, we are going to be looking at material on the origins of the kingdom of the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen, that is, the Cíannachta (a population group) of Glengiven in modern Co. Derry. The town of Dungiven, south of Limavady, and the barony of Keenaght preserve elements of the kingdom’s name and its approximate territory. Kings of the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen are attested in the Irish annals from the sixth through to the twelfth century, although it is likely that many, if not all, would have been sub-kings to the king of Ailech.

The actual, historical origins of Cíannachta Glinne Geimen as a polity are not at all clear (for recent discussion, see Patrick Gleeson’s article, ‘Luigne Breg and the origins of the Uí Néill’, pp. 1–5). However, Cíannachta was an identity also claimed by a kingdom in the Irish midlands. This was the kingdom of the Cíannachta Breg, in modern Cos Louth and Dublin, reduced during the eighth century to Ard Cíannacht, which roughly corresponded to the modern barony of Ferrard. Medieval historiographers traced the Cíannachta of both kingdoms, as a people, back to Tadg, son of Cían. Tadg was a son of Ailill Aulomm, legendary ancestor of multiple royal dynasties in Munster, who had come to the north to help Cormac mac Airt win back the kingship of Ireland from the Ulaid. This having been accomplished, Cormac granted him what would become the territory of the Cíannachta Breg, although Cormac allegedly cheated Tadg out of far more. The full story is related in the Middle Irish saga, Cath Crinna.

We begin our reading of the genealogies with Tadg’s offspring…

Sources

Of the genealogical collections currently in the IrishGen database, only those from the twelfth-century manuscripts, the Book of Leinster (L) and Rawl. B.502 (R) contain genealogies of the Cíannachta. These genealogies are generally similar in each manuscript, as both versions are re-workings of the same text.

The following sections, in particular, are of relevance. Note that the manuscripts divide up their material differently. In this instance, one section in L corresponds to several in R.

| Title | MS | Title in MS |

|---|---|---|

| IrishGen Base URL | ||

| Text 1 | L | Clanna Ébir i lLeith Chuind |

| http://example.com/LL/clanna_ébir_i_l-leith_chuind.trig | ||

| R | Clanna Ébeir H-I L-Leith Chuind | |

| http://example.com/Rawl_B502/clanna_ébeir_h_i_l_leith_chuind.trig | ||

| Text 2 | L | Clanna Ébir i lLeith Chuind |

| http://example.com/LL/clanna_ébir_i_l-leith_chuind.trig | ||

| R | Genelach Síl Cormaic Gaileng | |

| http://example.com/Rawl_B502/genelach_síl_cormaic_gaileng.trig | ||

| Text 3 | L | Genelach Eli Tuaiscirt |

| http://example.com/LL/clanna_ébir_i_l-leith_chuind.trig | ||

| R | Genelach Éle | |

| http://example.com/Rawl_B502/genelach_éle.trig | ||

| Text 4 | L | Genelach Ciannacht Glinne Geimen |

| http://example.com/LL/ciannachta_glinni_gaimen.trig | ||

| R | Genelach Ciannachta Glinni Gaimen | |

| http://example.com/Rawl_B502/genelach_ciannachta_glinni_gaimen.trig | ||

| Text 5 | L | Genelach Ciannacht |

| http://example.com/LL/ciannacht.trig | ||

| R | Genelach Ciannachta | |

| http://example.com/Rawl_B502/genelach_ciannachta.trig | ||

Tadg’s Sons: All is Well

We read in Text 1 in both manuscripts (R is quoted where there are no significant variants with L, as its online edition is easier to reference) that Tadg had two sons, Condla and Cormac (R §1345):

Tadgc m. Céin dano dá mc lais-side .i. Condla & Cormac

Cormac, ancestor of the Gailenga, does not concern us for the present purposes.

Condla’s Sons: The First Problem

Still according to both manuscripts, Condla also had two sons, Findchad Ulach and Fiacha (R §1346):

Condla dano m. Taidcg dá mc leis .i. Findchad Ulach & Fiachu.

Here we encounter our first problem. Fiacha appears here as a son of Condla. In a subsequent pedigree in Text 2 in R, however, Tadg has a son called Fiacha; in the corresponding pedigree in L, this Fiacha is the son of Condla.

… Echach Binnich m. Dubthaich m. Bressail m. Fiachach m. Thaidgc.

L:

… Echach Binnig m Dubthaig m Bresail m Fhiachach m Conlai. m Taidc.

What does this mean? It may well mean that the scribe of R simply made a mistake. However, it is our policy on IrishGen to take each manuscript version as seriously as possible; our data will then reveal what is an isolated mistake and what is an alternative tradition. Even so, we still have to make a decision as to whether “Fiacha son of Tadg” (R §1351) and “Fiacha son of Condla” (L, and elsewhere in R; e.g. R §1346) are the same person. They have the same name, different fathers, but the same descendants. The genealogist, at R §1351, could have invented a third son of Tadg or be making an assertion about the existing Fiacha’s parentage.

One could argue it either way but, on the basis that there is more the same about them than is different, I predicated them as the same individual:

<http://example.com/Rawl_B502/genelach_síl_cormaic_gaileng.trig#Fiachach>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:genName "Fiachach";

irishRel:nomName "Fiachu" ;

rel:childOf <#Thaidgc>;

owl:sameAs <http://example.com/LL/clanna_ébir_i_l-leith_chuind.trig#Fhiachach>.

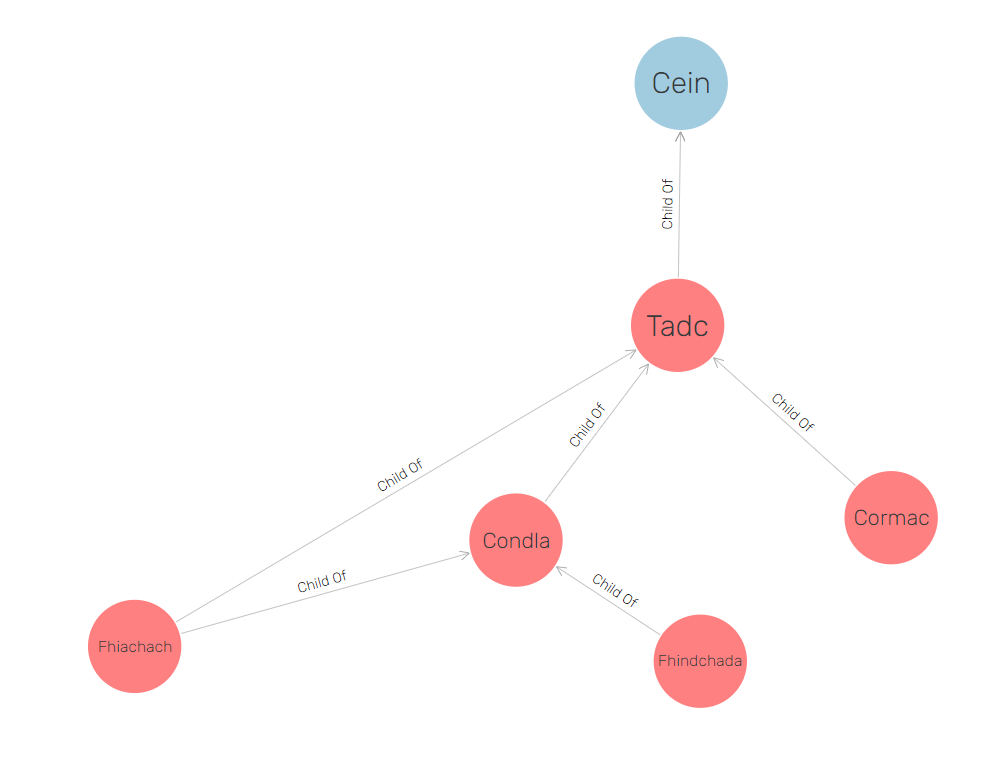

Our graph thus looks like this:

Data visualized with GraphDB

This might seem trivial — one name out of many — but it should be remembered that genealogy was a means of asserting political claims and identity in the Middle Ages. As the genealogies in L and R go on to set out, Fiacha is the ancestor of the Cíannachta Breg and Findchad Ulach is the ancestor of the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen. Making them brothers establishes parity between the kingdoms; making one the son of the other asserts claims dominance. In other words, R’s “mistake” at §1351 has distinct partisan undertones.

Findchad Ulach: Names and Sobriquets

Before we proceed towards the descendants of Findchad Ulach and the beginnings of the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen, there is an issue to resolve regarding Findchad himself. In most instances in the genealogies, he bears the sobriquet “Ulach” (spellings vary: “Ulag”, “Dulach” etc.). According to eDIL, this could mean “bearded”, “woodsman”, or even “outlaw”. This appears to have caused some confusion in L (Text 1), however, where we find a pedigree that ends as follows:

… m Findcháin m Feicc m Fhindchada m Fulig m Conla m Taidc m Céin.

Compare the corresponding pedigree in R, found in Text 2 (R §1354):

… Findcháin m. Féicc m. Findchada Ulaich m. Condla m. Taidg.

“Fulig” is not the genitive form of any attested medieval Gaelic given name and it is suspiciously similar to “Fulig’s” son’s sobriquet elsewhere. At some point in the textual tradition, a scribe has misunderstood the name “Findchad Ulach” (presumably in the form “Findchada Ulig” or thereabouts) and has taken the sobriquet to be another name in the pedigree. The addition of hypercorrect “f” to words that historically began with vowels is a well-attested feature of Middle Irish (c. 900–1200), due to “f” being silent (due to lenition) in various grammatical contexts, including when preceded by a genitive singular, as here.

This is clearly a mistake. Nonetheless, as mentioned, we have to take each manuscript version seriously. Therefore, in this situation, I added “Fulig” as a distinct individual in L’s Text 2 and even hypothesised what the imagined nominative form might look like:

<http://example.com/LL/clanna_ébir_i_l-leith_chuind.trig#Fulig>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:nomName "Fulech";

irishRel:genName "Fulig";

rel:childOf <#Conla-1644b090>.

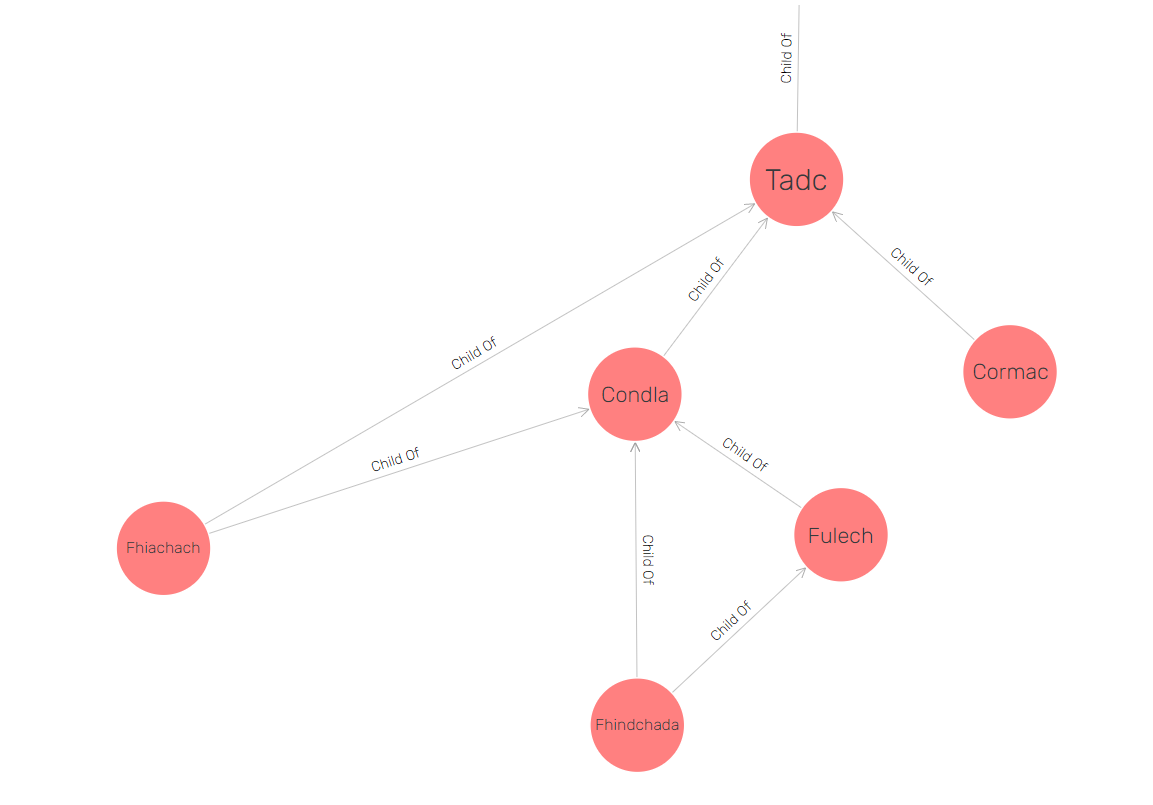

Our graph thus looks like this:

Data visualized with GraphDB

Findchad Ulach’s (Great-)grandsons: The Taking of Glengiven

L and R (Text 1) offer slightly different accounts of Findchad Ulach’s immediate descendants:

L:

Findchad m Findchada Ulaig. Is é tóesech ro gab Glend Gaimen. Oct meic leis .i. Fiacha. Etchu. Echen. Fergus. Cassoin. Sobarnach. Coartach. Find.

‘Findchad, son of Findchad Ulach: he is the first who took Glengiven. He had eight sons: Fiacha, Etchu, Echen, Fergus, Cassoin, Sabarnach, Coartach, [and] Find.’

Findchán mc Féicc m. Findchada Ulaich is h-é toíssech ro gab Glenn Gemen. Ocht mc leis .i. Fiac & Cú & Echen, Fergus, Mac Cass, Sabarnach, Coarthach, Find.

‘Findchán, son of Fíac, son of Findchad Ulach: he is the first who took Glengiven. He had eight sons: Fíac, Cú, Echen, Fergus, Mac Cass, Sabarnach, Coarthach, [and] Find.’

Several variants exist among the names of the eight sons. “Etchu” (L) versus “Cú” (R) could have arisen through the use of Latin et (“and”) somewhere in the tradition, for example. In general, each name in one version has a name in the other version that is sufficiently similar for them to be predicated as the same. L and R (Text 1) also disagree on the name of the eight sons’ father (“Findchad” versus “Findchán”) and on whether Fíac, son of Findchad Ulach, or Findchad Ulach himself is his father.

The idea in L (Text 1) that the eight sons’ father is “Findchad, son of Fíac” is an outlier even within L. While L might here refer to Erc, son of Echen, son of Findchad, son of Findchad Ulach, L subsequently (Text 4) provides a pedigree that conforms in doctrine to R §1347:

… Eirc m Echin m Fhindchain (is eside cetna gab Glend Gaimen) m Fheic m Fhindchada Ulig …

… Erc, son of Echen, son of Findchán (he is the first who took Glengiven), son of Fíac, son of Findchad Ulach …

The next pedigree in L (Text 5) is also based on the same doctrine:

… Dubain Ciannachta m Find m Findchain m Fheic m Findchada Ulaig.

Dubán Cíannachta, son of Find, son of Findchán, son of Fíac, son of Findchad Ulach.

Text 3 in L also appears to refer to Findchán, son of Fíac, although the manuscript is damaged at this point.

L’s omission of Fíac in Text 1, again, could well be a mistake. It is not applied elsewhere in that version of the genealogies (or in R) and it does not seem to be of much significance, as the overall structure of the genealogy does not change as a result. As for the difference in nomenclature, Findchad could be a mistake for Findchán; one can easily imagine a manuscript where the name is rendered “Findch-”, which the compiler of L (Text 1) expanded incorrectly in this instance.

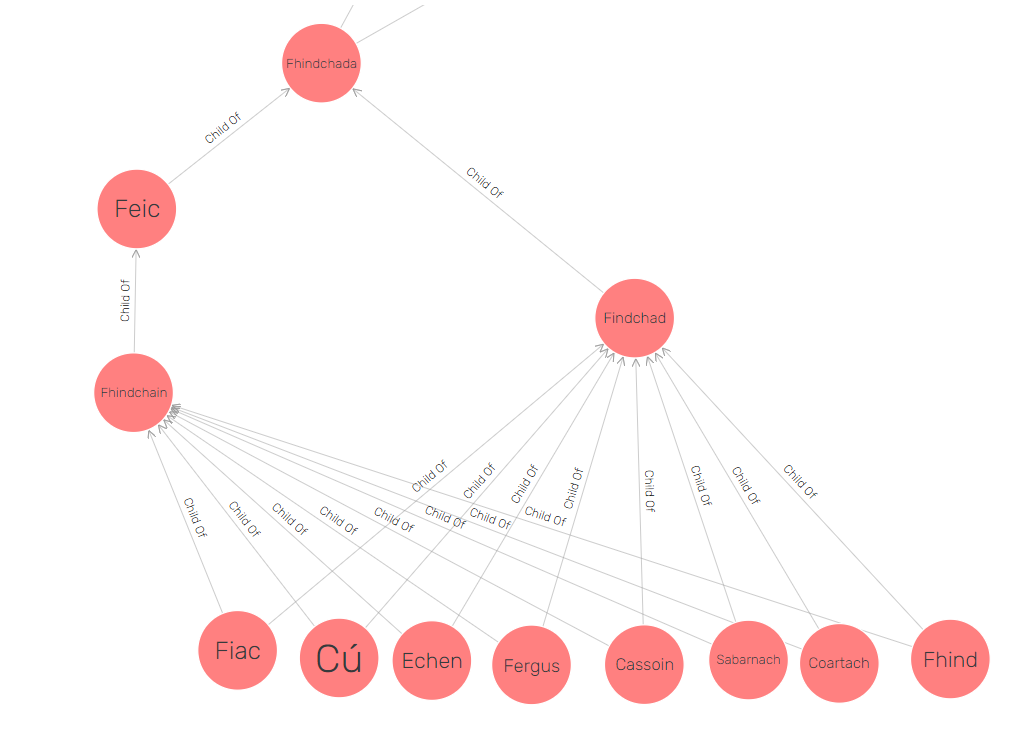

Nonetheless, although he has the same sons, L’s Findchad (son of Findchad Ulach) has a different name and a different father. I therefore encoded him as a different person from Findchán in R and elsewhere in L. This is what the resulting situation looks like:

Data visualized with GraphDB

Concluding Thoughts

With that, we have reached the beginnings of the kingdom of the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen, at least according to the medieval genealogists, and can conclude our reading. I hope this has illustrated the kind of situations we can find ourselves in when encoding semi-structured data from premodern manuscripts and how we tackle them. In general, we try to bring out the distinctive testimony of each manuscript version even where we strongly suspect a simple scribal error. As we’ve seen from these examples (“Fiacha, son of Tadg” versus “Fiacha, son of Condla”), in the world of politicised history and historicised politics that is the medieval Irish genealogies, what look like errors can be of potential significance for understanding the individual compiler’s agenda.

The hope is that we will eventually have data from enough manuscript versions in IrishGen to be able, among much else, to comment more confidently on which variants are of significance and which are mere errors. The tools available for analysing our data, as well as more adventures in encoding it in the first place, will be the subjects of future blogposts.