Human Curation and Digital Datasets: A Problem in Multiple Parts

Christopher Guy Yocum

ORCID: 0000-0002-7241-3264

One of the difficulties when creating and maintaining a human curated database is that humans are by nature error prone. In this article, I will explore some of the challenges and difficulties that the curators of the IrishGen database have encountered when dealing with ambiguous statements in the genealogies, how human error creeps in over time, and, finally, how IrishGen attempts to avoid introducing new errors.

This is not a new phenomenon within the area of the early Irish genealogies. Even in the pre-modern period, in which the scribes and redactors within the tradition were working, errors crept in over time. Donnchadh Ó Corráin has suggested that early Irish scribes attempted to avoid errors by using a highly repetitious structure (‘The Book of Ballymote: a Genealogical Treasure’ in Book of Ballymote: Codices Hibernenses Eximii II, pg. 10). Ó Corráin also discusses in that chapter a few hypothesises which IrishGen is well placed to test. Some of these errors were not even errors but motivated changes to the tradition by those who were paid to create or copy the genealogies in the first instance. Thus, it is often difficult to know as someone who is looking at the genealogies in the modern era what counts as an error and what counts as a motivated change to the tradition. As Eystein Thanisch stated in his article the policy of IrishGen is to take all statements in the manuscript tradition seriously. Thus, the curators attempt to preserve what is extant rather than attempting to editorialise.

Digital Curation and Data Governance

The first point is digital curation of historical material is not a new subject. The University of Edinburgh’s Digital Curation Centre is entirely devoted to the curation and preservation of digital artefacts. Additionally, the International Journal of Digital Curation is one forum for discussion of these issues. Other fora can be found on the DCC’s publication website.

The second point is that corporate data governance is also a well known discipline which attempts to curate and standardise data within a corporate environment. The Data Steward ensures that the data can be both stored and handled securely in terms of law (e.g. HIPAA in the United States and GDPR in the European Union) and the data is in a form so that it can be used profitably by the corporation.

Both of these disciplines have much in common and often overlap in terms and structure. In terms of IrishGen, digital curation is probably more important but both disciplines emphasise having data policies which guide the collection and organisation of data artefacts. As stated by Eystein Thanisch, the primary policy of IrishGen is to take the original data seriously, even if that means, when working with digital editions like those on CELT, going back to the original manuscript source to check on possible transcription errors originating from the translation of the information from manuscript to printed source to digital source.

For a more concrete example, a curator with data curation experience would assist other curators when setting policy for different RDF constructs concerning where and when to use them and help communicate those policies to other curators or other contributors. The data curation expert would also help create tools and policies concerning data quality and data integrity. For instance, reading, reviewing, and when necessary changing data so that it conforms to best practice, such as the W3C Data on the Web Best Practices and Linked Data Platform Best Practices and Guidelines.

Unfortunately, due to lack of resources and lack of time on the current curators’ part, the insights from these two disciplines have not been explored in detail. When creating databases like IrishGen, having a curator or a willing volunteer from one of these disciplines can be a boon to disrupting patterns of error and encouraging best practice before the data reaches a point at which an end user, such as a scholar or other interested party, encounters the data.

Automation

Unlike the scribes and redactors of medieval Ireland, who mainly relied on repetition and structure to reduce errors, IrishGen relies on the structure to create automated tools to encode digital versions of the genealogies, most prominently the CELT digital versions of semi-diplomatic transcriptions, into RDF.

However, automation is no panacea as even slight variations in the source material can cause the automation to introduce its own errors. In IrishGen, a balance is struck between full automation and full manual with special case utilities that take some of the manual work out but leaving the integration to the curator. In this case, there are two cases which are particularly easy for a computer to handle. First, is the “String Pedigrees” (Matthew Holmberg, ‘Towards a Relative Chronology of The Milesian Genealogical Scheme’, pg. 18), for instance from The Book of Leinster’s (LL) Genelach Dal Copri Arad:

Flaithbertach m Crunmael m Commáin m Fhinain m Faigfhir m Ernine m Feic m. Ieir m Gussa m Fobrich m Maeil m. Ainmerech m Fir Roith m Muine m Fir Nued m Fir Lugdach m Buain m Argatibair m Corpri Cluchechair m Con Corbb.

Encoding of this kind of String Pedigree is easy to automate and IrishGen has a tool for doing some of this. It is up to the curator to integrate the output into the file that they are working on and find any links between the individuals in the String Pedigree and other parts of the database. This integration process is a human intervention and can cause errors to creep in. For instance, using the utility name-list.pl from IrishGen itself, the sequence of actions is (the output is truncated for the reader’s convenience):

➜ irish-gen git:(master) ✗ perl -CA utils/name-list.pl "Flaithbertach m Crunmael m Commáin m Fhinain m Faigfhir m Ernine m Feic m. Ieir m Gussa m Fobrich m Maeil m. Ainmerech m Fir Roith m Muine m Fir Nued m Fir Lugdach m Buain m Argatibair m Corpri Cluchechair m Con Corbb"

<#Flaithbertach>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:nomName "Flaithbertach";

rel:childOf <#Crunmael>.

<#Crunmael>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:genName "Crunmael";

rel:childOf <#Commáin>.

<#Commáin>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:genName "Commáin";

rel:childOf <#Fhinain>.

<#Fhinain>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:genName "Fhinain";

rel:childOf <#Faigfhir>.

<#Faigfhir>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:genName "Faigfhir";

rel:childOf <#Ernine>.

...

One thing to note here is that the utilities may evolve and change over time to become more sophisticated depending or even be deleted entirely based on the interests and needs of those involved.

The way in which this works is to split the String Pedigree by the “m” or other textual means of indicating “son of”. The list of names is then ordered and slotted into a template which is then appended to the output. Once the program has reached the last name in the list, it outputs the results.

The second point of automation is the numerical components of pedigrees, for instance from LL’s Genelach h-Úa Lomthuile:

Trí mc la Cummine .i. Laidcnén. Conandil. Suibne.

Three sons with Cummin .i. Laidcnén. Conandil. Suibne.

The utility can recognise up to the number ten and produce snippets of RDF for the curator to integrate into the database. For instance, using IrishGen’s numbered.pl:

➜ irish-gen git:(master) ✗ perl -CA utils/numbered.pl "Trí mc la Cummine .i. Laidcnén. Conandil. Suibne."

<#laCummine>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:genName "la Cummine";

irishRel:numChild 3.

<#Laidcnén>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:nomName "Laidcnén";

rel:childOf <#laCummine>.

<#Conandil>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:nomName "Conandil";

rel:childOf <#laCummine>.

<#Suibne>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:nomName "Suibne";

rel:childOf <#laCummine>.

This utility works by having the first ten numerals in Old

Irish directly encoded within

it. This encoding of the numeral is very literal and does not account

for varient spellings of any kind at the moment. The utility then

splits on the “.i.” to separate the parent from the children.

Subsequently, it splits on the “mc” (or a few other variants that have

been encountered in the sources). The numeral which comes before the

“m” becomes the numChild, the numeral is matched to the Old Irish

word and translated into a more familiar Arabic numeral, while the

rest of the parent indicator becomes the name. As one will notice

with irishRel:genName "la Cummine" this causes the incorrect name to

be generated so human intervention is necessary to clean up the output

before integrating it into the dataset. Additionally, if there are

multiple URLs with the same structure, human intervention with be

needed to enforce uniqueness. The method of creating URLs for

individuals will be covered in a following post. The rest of

processing done by the utility is slotting the children and parent

into their RDF templates then outputting the result.

Another area of automation is the way in which the database is stored. Because the files are stored in text file format for RDF called TRiG, they can be stored in a Version Control System (VCS) which controls and coordinates all changes to the dataset. This allows all data to be tracked by the curators and errors can be traced to their source and corrected. In the case of IrishGen, the Git version control system is used and the Github website is used to give a more user friendly interface to the system.

A final area and often the final formal check before data is committed as the latest version of the dataset is the format checking. TRiG is very specific file format and it can be very easy for a human to break it. In this case, a TRiG parser is used and any errors in file format is indicated to the curator for fixing. While this does not always guarantee the files are not broken, it does give one last check before the data is merged.

Peer Review

Another method used is peer review. Using the Github Pull Request (sometimes also called Merge Request), changes to the data can be reviewed before it is merged into the dataset as the current version. The pre-modern scribes and redactors also took a peer review approach as can be seen in whole areas of manuscripts being scraped and rewritten or comments put either interlinearly or on the sides of columns in a manuscript. It works similarly where merge requests are given to a reviewer who goes over the information and approves it before it becomes part of the current dataset. As this is a human process, albeit one assisted by automation, errors still slip through.

Again, this process is constrained by the curator time available. For IrishGen to move forward and avoid stagnation, lack of peer review cannot be a barrier to continued development. Thus practical flexibility is necessary. If there is no peer reviewer available then the curator can just merge changes into the dataset without review. Additionally, as the dataset is publicly available, forking (see also Github “Fork a repo”) is another possibility for changing the dataset.

While peer review is a time honoured method to attempt to stop errors from entering a collaborative work, like the early Irish genealogies historically and IrishGen now, it cannot entirely stop errors from curators being introduced.

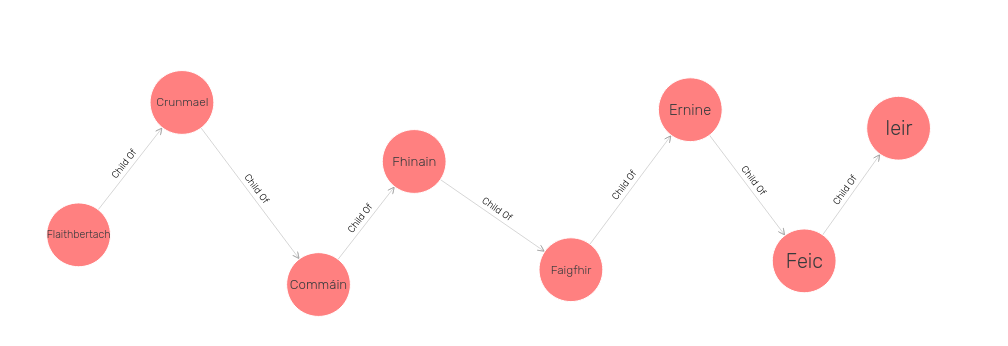

Audit

This particular technique does not catch errors but detects them after they have become part of the dataset. One way of doing this was recently undertaken by Eystein Thanisch who used the GraphDB triplestore which allows for storing, searching, and visualising RDF. This works by using the SPARQL query language and GraphDB’s visualisation to allow visual inspection of the data. For instance, looking at part of Flaithbertach’s genealogy from above, it may be visualised thus:

However, due to the structure of the data, errors can be detected more easily if the visualisation does not make sense. Many times this can be identified as a cyclical structure in the descendants of an individual where one of the descendants ends up being both an indirect and direct descendant of an individual. In other words, a descendant several generations away from their ancestor is also encoded as their direct ancestor which creates a cyclical structure in the genealogy. This visual inspection is the basis for Thansich’s previous article and for his current work on IrishGen. An concrete example of this will be covered in a future post.

The audit approach is manual and labour intensive. While invaluable, it is not a sustainable process as it heavily relies on people who are both available, trained, interested, and knowledgeable concerning the medieval Irish genealogies.

Conclusion

In a future article, I will cover some of the properties of RDF specifically in conjunction with human curation which can contribute to errors appearing in the dataset.

IrishGen stands at the end of a long history of copying, redaction, and adaptation of the early Irish genealogies, starting in early medieval Ireland itself. Like those who came before, we attempt as best we can to be accurate and to do justice to our source materials. However, we are human and errors and misunderstandings can and will cause errors to appear in the end product. While the techniques discussed broadly above will lessen the likelihood of errors, they cannot wholly eliminate the possibility thus users of the datasets will need to be diligent and aware of the possibility of error in their use of the dataset.