Some Examples of Querying and More on the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen

Eystein Thanisch

ORCID: 0000-0003-2819-5519

Introduction

In a previous blogpost, we looked at the variants between and within manuscript versions of the medieval Irish genealogies that we can encounter while working on IrishGen and how we go about encoding the information involved. This was in the context of the genealogies’ account of the origins of the kingdom of the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen. In this post, we’re going to continue following the history of this kingdom but, this time, consider some simple examples of how the IrishGen database can be queried.

For introductory reading on the genealogies, we recommend Nollaig Ó Muraíle’s published lecture, The Irish Genealogies: Irish History’s Poor Relation?, and Matthew Holmberg’s PhD thesis, ‘Towards a Relative Chronology of the Milesian Genealogical Scheme’ (pp. 3–54). For an overview of IrishGen and our use of RDF, see the project README; for more in-depth discussion, see Christopher Yocum’s previous blogposts on linked data and digital datasets. All our data is available in our GitHub repository.

Sources

The Book of Leinster (L) and Rawl. B.502 (R) continue to be our main manuscript sources, as these contain the only genealogical collections currently in the IrishGen database that include significant quantities of material on the Cíannachta. The third major genealogical collection in IrishGen, that from Laud Misc. 610 (Ld), also makes an appearance.

A table of texts from the genealogies cited in this post is given at the end of this post.

The Sons of Findchán

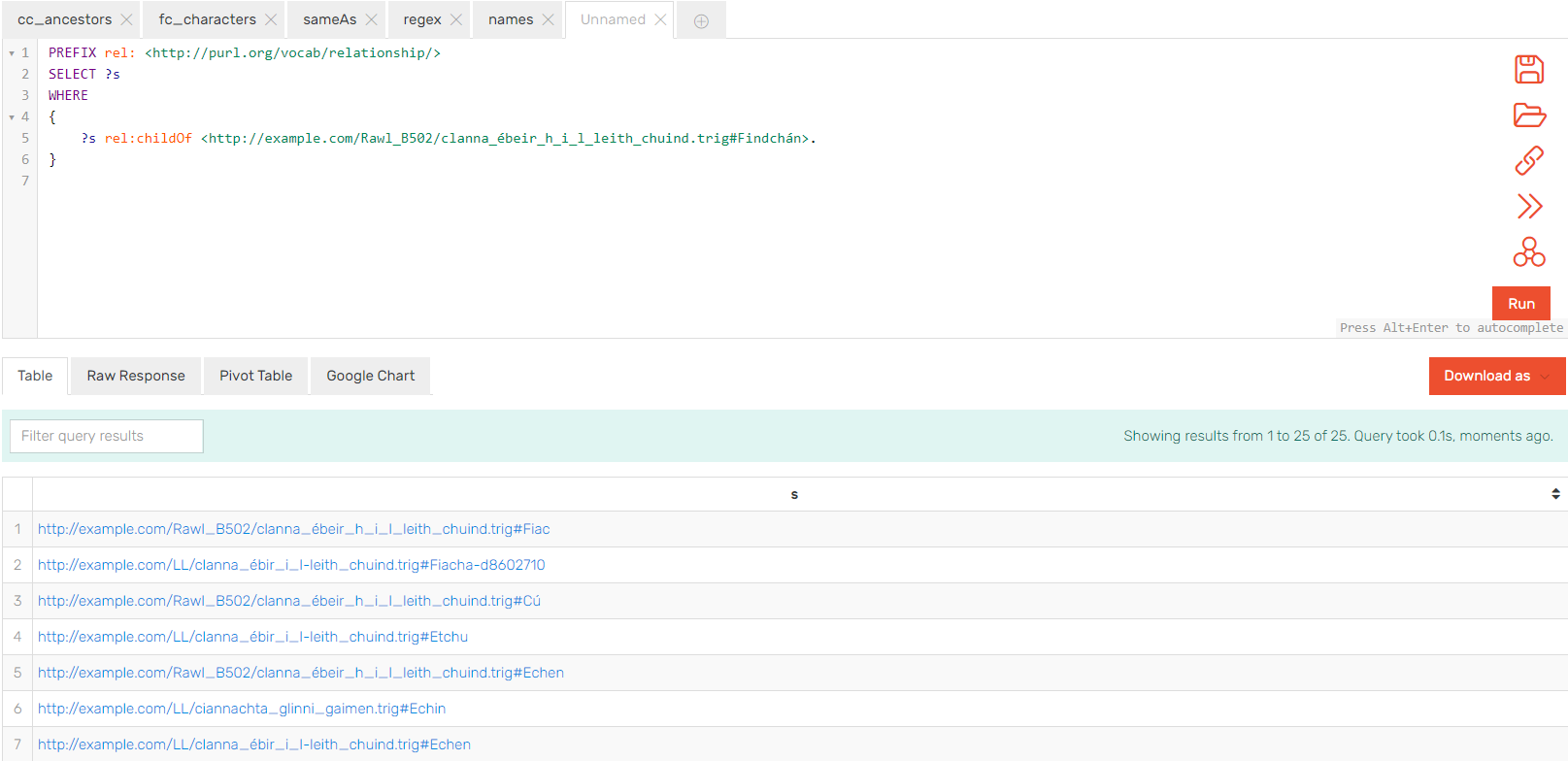

We have seen, notwithstanding isolated variants, that, in the genealogies (Text 1), the first descendant of Tadg mac Céin to acquire territory in Glengiven was Findchán, son of Fíac, son of Findchad Ulach and that he had eight sons. We can check the statement that he had eight sons against the rest of the IrishGen database. This can be done using a visual explorer, such as that provided by GraphDB, which was used to produce the visualizations previously (for more on how this works, see GraphDB’s documentation). It can also be done using a SPARQL query:

PREFIX rel: <http://purl.org/vocab/relationship/>

SELECT ?s

WHERE

{

?s rel:childOf <http://example.com/Rawl_B502/clanna_ébeir_h_i_l_leith_chuind.trig#Findchán>.

}

This returns not just every child of Findchán given in R §1347 (Text 1), which is the mention of Findchán to which the URL used relates. It returns the URL of every child of someone predicated as the same as Findchán (owl:sameAs) across IrishGen and of everyone predicated as the same as each of those children, or predicated as the same as someone who is the same as Findchán or as one of his children and so on.

25 URLs are returned:

Query executed with GraphDB

Query executed with GraphDB

These are mostly recognisable as mentions of the eight sons listed in Text 1. However, the query also reveals an item in R (Text 2), far removed within that manuscript from other sources for the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen, that mentions a ninth son of Findchán, Nóes.

Cummair Diabulban m. Conglais de Chiannacht Glinni Gemen. Is de atá Cummair Diabulbane & Druim Senchuimre qui habuit duas uxores unaque in his duabus non erat frequens et ob hoc Diabulbane dictus est. Cummair Diabulban didiu m. Conglais m. Nóes m. Fincháin m. Féicc m. Imchada Ulaich m. Condlae m. Thaidc m. Céin m. Ailella.

Cummair Diabulban [“meeting of two women”?], son of Conglas, of the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen. From this is [named] Cummair Diabulbane (and Druim Senchuimre [“the hill of old Cummair”?]) who had two wives and one of these two was not attentive and from this he was called “diabulbane” [“of a double-wife”]. Cummair Diabulban, indeed, son of Conglas, son of Nóes, son of Findchán, son of Fíac, son of Imchada Ulach [read “Findchad Ulach”], son of Condla, son of Tadg, son of Cían.

This is a difficult passage and the interpretation above is provisional. In particular, the genitive singular of Irish ben should be mná, not *ba[i]ne. The genealogies in the Book of Lecan (not yet part of IrishGen) also contain this passage and read “Diabalmuine” (“of the double gift”?; see eDIL, s.v. díabul).

In any case, we’ve shown how a query can retrieve information about an individual and about individuals connected to them in some way from across IrishGen’s database. Obviously this can only be done with material that has already been added to IrishGen and which we have encoded correctly, including correctly predicating which mentions of people relate to the same individuals. We are thus searching material with which we’ve already worked quite closely. However, querying is invaluable even for us, as IrishGen already contains almost 25,000 individuals and we have been working on it for several years, so we need to be able to keep track of our data.

Searching for the Satirist

Returning to Text 1, some intriguing information is provided about the fortunes and progeny of one of Findchán’s sons (R §1347):

Coarthach mc-side Loiscibet .i. bancháinte do Chiannacht Glinni Gemen do Cheníul Fergusa m. Lemna m. Cóelbad do-bert tír dó conid de at-berar Coartrige.

Coarthach was the son of Loiscibet, that is, the female satirist of the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen, of the kindred of Fergus, son of Liaman, son of Cóelbad, who gave land to him, so that from him the Coartraige are named.

I originally planned to make this post about identifying Loiscibet and her ancestors by querying IrishGen’s data. However, extensive querying of IrishGen and consultation of other sources has failed to turn up any convincing identifications. This might be illustrative of the frustrations that can occur while working with this sort of source material, but it wouldn’t be very useful for demonstrating querying.

What we can do is use IrishGen to contextualise Loiscibet in terms other than of ancestry. The entry relating to her appearance in the above passage is as follows:

<http://example.com/Rawl_B502/clanna_ébeir_h_i_l_leith_chuind.trig#Loiscibet>

a foaf:Person ;

irishRel:genName "Loiscibet" ;

foaf:gender "female" ;

foaf:title "bancháinte"@sga, "female satirist"@eng;

owl:sameAs <http://example.com/LL/clanna_ébir_i_l-leith_chuind.trig#Loscibet>;

rdfs:comment "bancháinte do Chiannacht Glinni Gemen" ;

rel:parentOf <#Coarthach>.

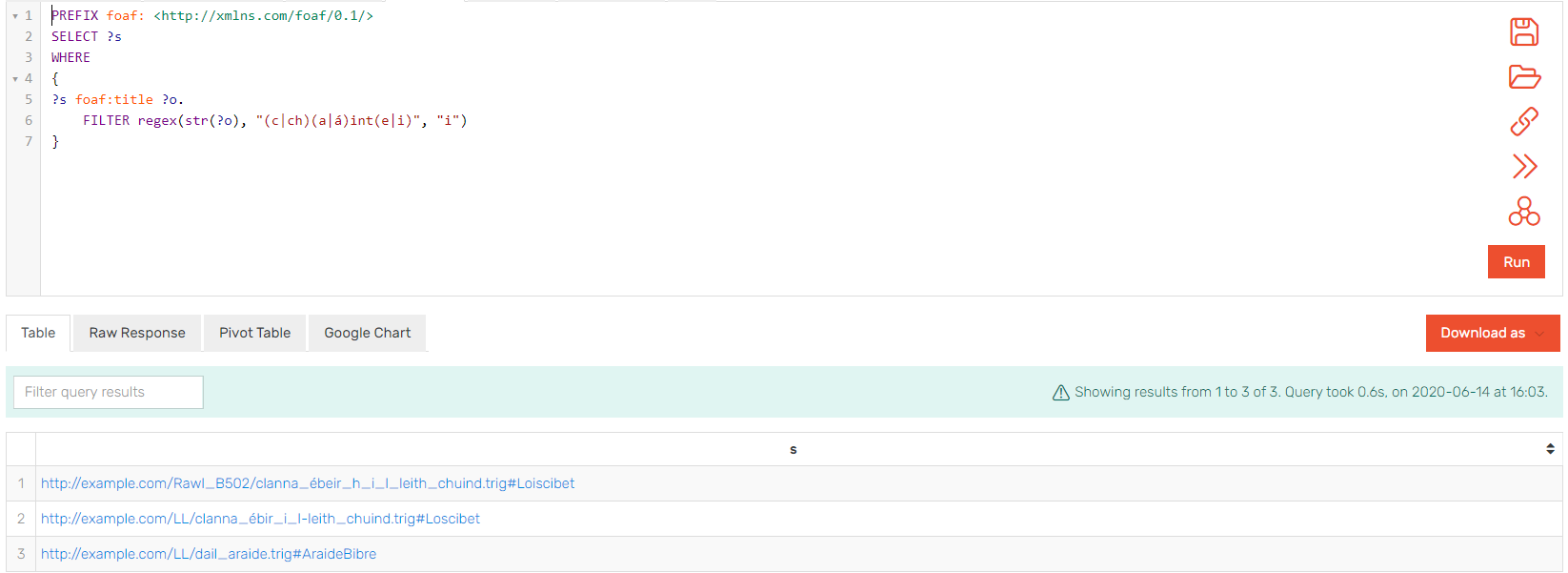

She is described as a bancháinte (“female satirist”), from ben (“woman”) and cáinte (“satirist”). Do any other satirists appear in IrishGen’s database? We can find out:

PREFIX foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/>

SELECT ?s

WHERE

{

?s foaf:title ?o.

FILTER regex(str(?o), "(c|ch)(a|á)int(e|i)", "i")

}

This SPARQL query looks for any URL where the string literal predicated as its foaf:title contains the string “cáinte”, REGEX being used to allow for the presence or absence of capitalisation, lenition, and the length mark, and Middle Irish variation in final vowel quality. In other words, it looks for all instances of people who have been given the title “satirist”.

As it happens, IrishGen does contain another instance of a satirist:

Query executed with GraphDB

Query executed with GraphDB

Following the URL returned back to the file, we find:

<http://example.com/LL/dail_araide.trig#AraideBibre>

a foaf:Person;

irishRel:nomName "Araide Bibre";

foaf:title "cáinte"@sga, "satirist"@eng;

foaf:title "rechtaire"@sga, "steward"@eng;

rel:employedBy <#Cormac>;

rdfs:comment "in cáinte de Mumnechaib ba sé ba rectaire do Chormac .h. Chuind".

This is from the following source in L (Text 3):

Dondchad m Aeda m Longsig m Etig m Lethlobair m Longsig m Thommaltaig m Indrechtaig m Lethlobair m Echach Iarlathi m Fhiachnai m Boetain m Echach m Condlai m Coelbaith m Cruind Ba Drúi. m Echach m Lugdach m Rosa m Imchada m Fheidlimthi m Meic Caiss m Fhiachach Araide. Araide Bibre in cáinte de Mumnechaib ba sé ba rectaire do Chormac .h. Chuind. Cairech a ben. Is i ro anacht Fiacha mc Oengusa. inde dicitur Fiacha Araide a quo Dal Araide. m Oengusa Gobnenn m Fhergusa m Tipraite (qui occidit Cond) m Bresail m Fheirbb m Máeil m Rochride m Cathbath m Aillchatho m Findchada m Muridaig m Fhiachach Find m Amnais m Iriel Glúnmair m Conaill Cernaig.

Dondchad, son of Áed, son of Loingsech, son of Etech, son of Lethlobar, son of Loingsech, son of Tommaltach, son of Indrechtach, son of Lethlobar, son of Eochu Iarlaith, son of Fiachna, son of Baetán, on of Eochu, son of Condla, son of Coelbad, son of Crond Ba Drúi, son of Eochu, son of Lugaid, son of Ros, son of Imchad, son of Feidlimid, son of Mac Caiss, son of Fiacha Araide (Araide Bibre, he was the satirist from among the Munstermen. He was steward to Cormac, grandson of Conn. Cairech was his wife. It was she who cared for Fiacha, son of Óengus [Gobnenn]. Thence he is called Fiacha Araide, whence are called the Dál nAraide.), son of Óengus Gobnenn, son of Fergus, son of Tipraite (who killed Conn [Cétcathach]), son of Bresal, son of Ferb, son of Máel, son of Rochride, son of Cathbad, son of Alchath, son of Findchad, son of Muiredach, son of Fiacha Find, son of Amnas, son of Irial Glúnmar, son of Conall Cernach.

This is the pedigree of Dál nAraide that featured in a previous blogpost. The text in bold is a marginal insertion, which both the scribe and the editors of L place in a Cenél Lóegaire pedigree but which we feel makes far more sense if read here.

This passage is an origin legend and etymological narrative for the Ulster kin-group of Dál nAraide, whose kingdom was located to the east of that of Cíannachta Glinne Geimen, stretching from Mag nEilne, on the north coast between the River Bush and the River Bann, down to Lough Neagh. They were a major power in Ulster in middle of the first millennium. Genealogically, according to this text, they are rooted in the north, descending from the Ulster Cycle hero, Conall Cernach. However, like the Cíannachta, their story is also linked via etymology in to that of Cormac mac Airt (= Cormac, grandson of Conn) and the legendary kingship of Ireland, which in turn connects them to far-off Munster. The compilation of genealogical collections as we have them was, after all, part of the developing national pseudo-history of Ireland, in which the idea of an island-wide kingship was key. For introductory reading on this subject, see John Carey’s The Irish National Origin-Legend: Synthetic Pseudohistory.

Araide Bibre, our satirist, is the linchpin of the etymological, ‘national’ side of this narrative. The significance of him being a satirist is unclear. It does not mean that he was ignoble. Satire was the inverse of praise poetry in medieval Ireland but still took place in the context of elite politics, supposedly within a regulatory framework. For a detailed recent study, see Roisin McLaughlin’s Early Irish Satire. A satirist, whatever the term’s modern connotations, would have been very much part of the establishment, even though illegitimate use of satire appears to have been a concern among jurists (see Early Irish Satire, pp. 3-8).

In Text 3, Araide Bibre, is clearly male. He is denoted with the masculine pronoun, sé, and he has a wife, Cairech. She is the one who actually fosters Fiacha. Elsewhere, however, Araide Bibre appears as a woman and as Fiacha’s fostermother. ‘A fhir thall tríallus in scél’, which consists almost entirely of questions relating to Irish legendary history, poses the following (stanza 22, translation my own):

Cía ainm na mná, monur ngle ro alt Fiacho Araide?

What is the name of the woman, a pure undertaking, who brought up Fiacha Araide?

In the 16th-century manuscript, (Egerton 1782), the questions are answered in glosses. This question is glossed as follows (translation my own):

Araide Bibre ainm a muimme, is de ro lil Fiacho Araide.

Araide Bibre was the name of his foster-mother; it is through her that Fiacha Araide survived.

It is not clear how these traditions relate to each other or which is of greater antiquity. We are, however, presented with the intriguing situation in which two neighbouring kingdoms, Cíannachta Glinne Geimen and Dál nAraide, have origin legends in which satirists (one female and one sometimes female) play an important supporting role. This could, of course, be mere coincidence.

In any case, this brief investigation shows how IrishGen can be queried for details other than names and genealogical relationship and thus used to compare details of narratives preserved across the genealogical collections.

Identifying Individuals at the Burning of the Kings

Returning to the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen, after the eight (or nine) sons of Findchán, their history, as preserved in the genealogies, consists of string pedigrees unaccompanied by further comment. The individuals who appear in these pedigrees, however, can be located in other sources, such as the Irish annals. In this final section, we are going to look at one annal entry mentioning a king of Cíannachta Glinne Geimen and show how IrishGen can be used to identify the other characters in the entry.

The entries in the Annals of Ulster for AD 681 include the following (681.1):

Combustio regum i n-Dun Ceithirnn, .i. Dungal mc. Scannail, rex Cruithne, & Cenn Faelad, rex Cianachtae, .i. m. Suibni, in initio estatis la Mael Duin m. Maele Fitrich.

The burning of the kings in Dún Ceithirn, i.e. Dúngal son of Scannal, king of the Cruithin, and Cenn Faelad, i.e. son of Suibne, king of Ciannachta by Mael Dúin son of Mael Fithrich, at the beginning of summer.

Cenn Faelad, son of Suibne, appears in one of the royal pedigrees of the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen in L and R (Text 4), so that is all cogent enough. Who, then, are Dúngal, son of Scandal, alongside whom Cenn Fáelad was burned, and Mael Dúin, son of Mael Fithrich, who is said to have been responsible? There are, of course, numerous works of secondary literature that could be consulted for context on this entry. For the purposes of this blogpost, however, we will search for the individuals named in IrishGen.

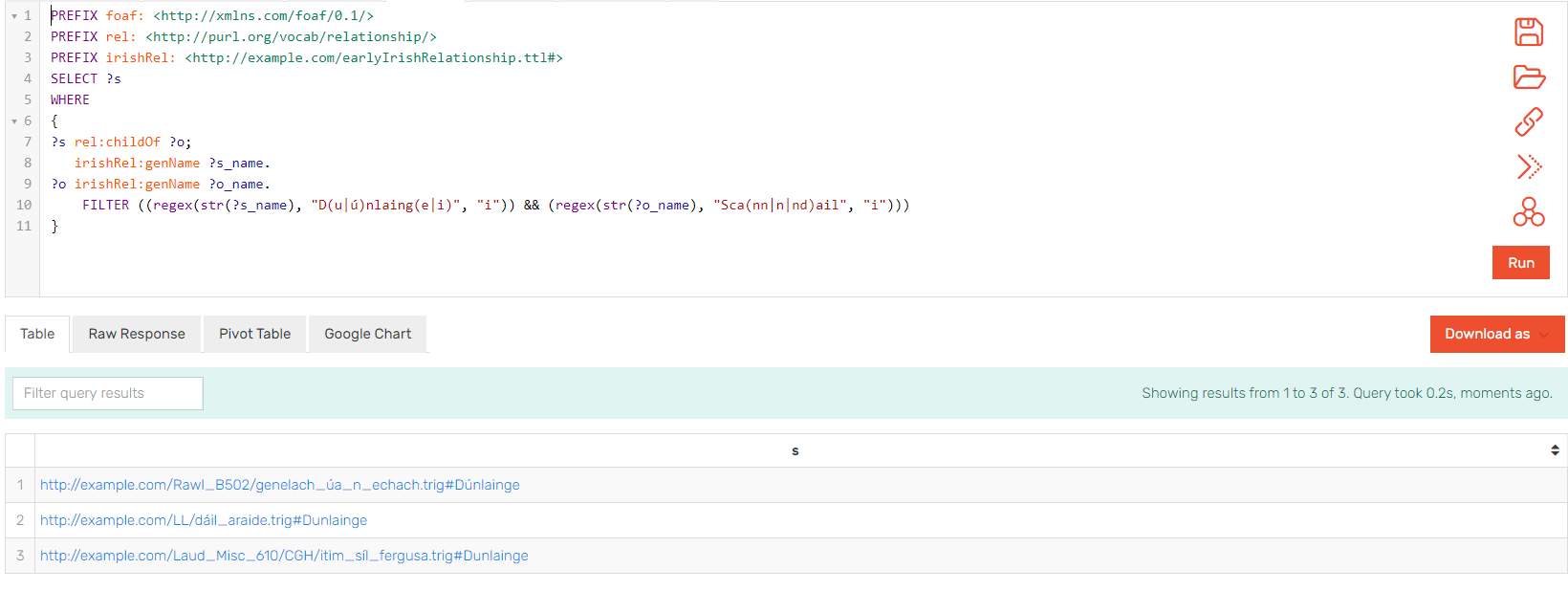

The following SPARQL query searches IrishGen for every instance of someone called Dúnlang who is the child of someone called Scandal. Names usually appear in the genealogies in the genitive, we will begin by searching just the genitive forms of the two names. As with our query on cáinte, an effort is made to anticipate possible variant spellings.

PREFIX foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/>

PREFIX rel: <http://purl.org/vocab/relationship/>

PREFIX irishRel: <http://example.com/earlyIrishRelationship.ttl#>

SELECT ?s

WHERE

{

?s rel:childOf ?o;

irishRel:genName ?s_name.

?o irishRel:genName ?o_name.

FILTER ((regex(str(?s_name), "D(u|ú)nlaing(e|i)", "i")) && (regex(str(?o_name), "Sca(nn|n|nd)ail", "i")))

}

Had this query not returned satisfactory results, we might have considered searching nominative forms too. However, the results show that someone called Dúnlang, son of Scandal, appears once each in three versions of the genealogies:

Query executed with GraphDB

Query executed with GraphDB

Navigating to the files and source texts involved, we find that Dúnlang appears in the genealogies of Dál nAraide (Text 5) and is a descendant of Fiacha Araide, mentioned above. This was already implied in AU 681.1, where he is called rex Cruithne (‘king of the Cruithni’), Cruithni being the broader ethnic designation for the group of peoples among whom Dál nAraide had become the dominant kingdom.

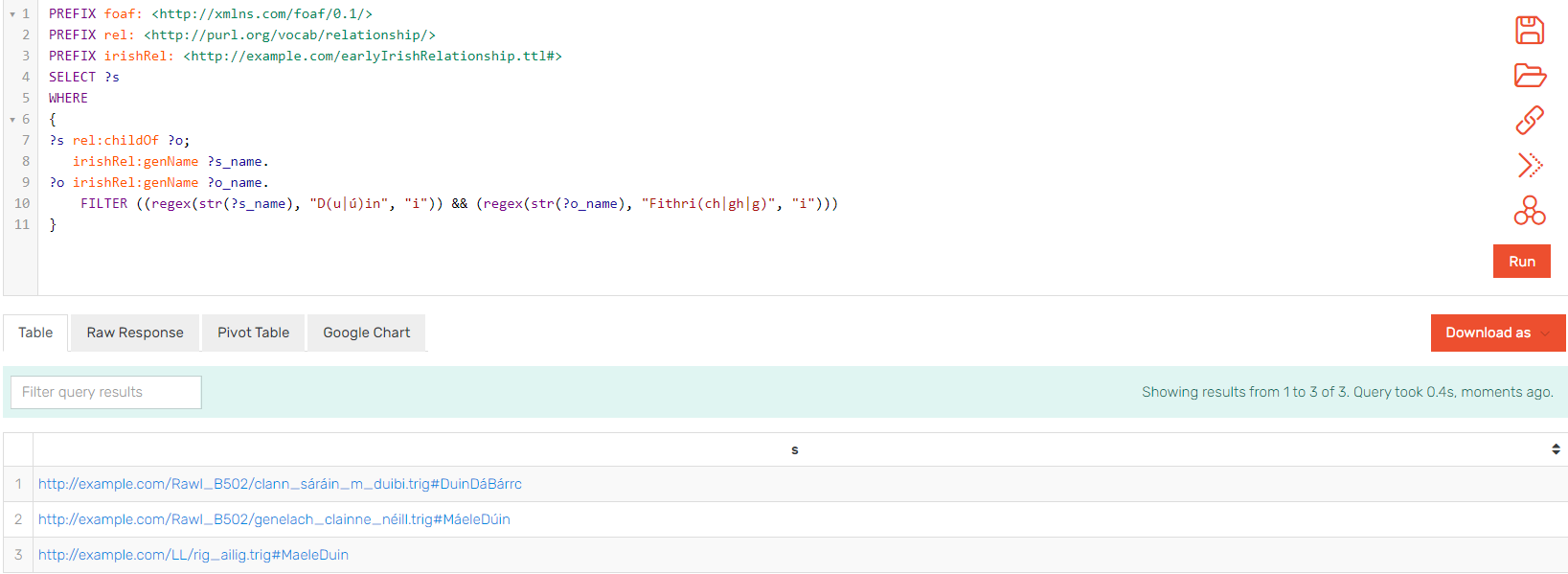

Mael Dúin, son of Mael Fithrich, carries no such identification in AU 681.1. The following query is similar to the previous query. For the sake of speed and concision, it searches for just the specific second element of both names, dropping the initial generic, Mael.

PREFIX foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/>

PREFIX rel: <http://purl.org/vocab/relationship/>

PREFIX irishRel: <http://example.com/earlyIrishRelationship.ttl#>

SELECT ?s

WHERE

{

?s rel:childOf ?o;

irishRel:genName ?s_name.

?o irishRel:genName ?o_name.

FILTER ((regex(str(?s_name), "D(u|ú)in", "i")) && (regex(str(?o_name), "Fithri(ch|gh|g)", "i")))

}

This returns three results:

Query executed with GraphDB

Query executed with GraphDB

The first result turns out to be irrelevant, a consequence of the corners we cut when devising the query. It relates to ‘Duin Dá Bárrc m. Fithrich’ (Dún Dá Bárcc, son of Fithrech), of the obscure Clann Sárain meic Duibi (Text 6). The other two results, however, both relate to Mael Dúin, son of Mael Fithrich, who appears in a royal pedigree of Cenél nÉogáin (Text 7), one of the northern branches of the Uí Néill. They were based in Inishowen, latterly expanding into modern-day Co. Tyrone, to the west of Cíannachta Glinne Geimen. Cenél nÉogáin had been the junior partner to Cenél Conaill within the northern Úi Néill but Mael Dúin was one of a series of series of Cenél nÉogáin kings in the seventh and eighth century who increased their faction’s power through expansion of their influence eastwards. His confrontation in 681 with Cíannachta Glinne Geimen and Dál nAraide should be seen in this context. Mael Dúin did not prosper personally from the ‘burning of the kings’, however, as he was to die himself later the same year (AU 681.2) at the battle of Blai Sléibe. According to the Annals of Tigernach, his opponents at that battle were again the Cíannachta Glinne Geimen (AT 681.1).

Concluding Thoughts

This post has presented three situations in which a simple query of IrishGen provides valuable context when reading both genealogical and other types of source material. This is intended as a quick, practical showcase of IrishGen’s usefulness as a database. Querying is complex, both in theory and in its myriad applications, and Christopher Yocum will be covering it in much more detail in future posts.